World Refugee Day: Reflecting on inequalities in Lebanon

Early Marriage

Kaida*, a 19-year-old married Syrian girl living in a collective shelter in Baalbek. She married at the age of 16 and has one daughter.

*All names are pseudonyms to protect confidentiality

Girls who marry at a young age often do not understand the sexual nature of marital relations. In addition, girls are not prepared to communicate with their husbands and assume adult responsibilities. Although they are taught cooking and housework at their parents’ homes, taking on responsibility for a whole new household with their husband’s family can be overwhelming– which can lead to verbal and physical violence. When they have children, girls do not know how to care for them because they are still children themselves. Younger girls do not know how to stand up for themselves. Their husbands and in-laws control them, forcing them to give up their friends and confining them to home. Girls should not marry before the age of 18 until they are mentally and physically mature!

Child marriage costs girls their opportunities to learn. I have never been to school in Lebanon. My father was too afraid that the Lebanese students would treat me badly—and school here is very expensive. If I had stayed in Syria, my life would have been very different. Every village has a free school and because everyone trusts one another, no one is afraid to send their daughters to school. None of my older female relatives married as children; they all finished their education first. I lost my life when we came to Lebanon.

Social inequalities and effects of the crisis

Ali, a 19-year-old in-school Lebanese boy living in Baalbek.

Political parties are using the crisis to reward those who are uneducated but loyal and destroy those who are educated and want a peaceful more equitable country. Even now there is traffic everywhere, because those paid by the party in US Dollars are able to afford fuel and go where they wish—while university professors have seen their salaries fall from 10,000 to 200 and must walk to work. This injustice and cruelty is crushing those who bring value to our society and destroying the dreams of educated young people.

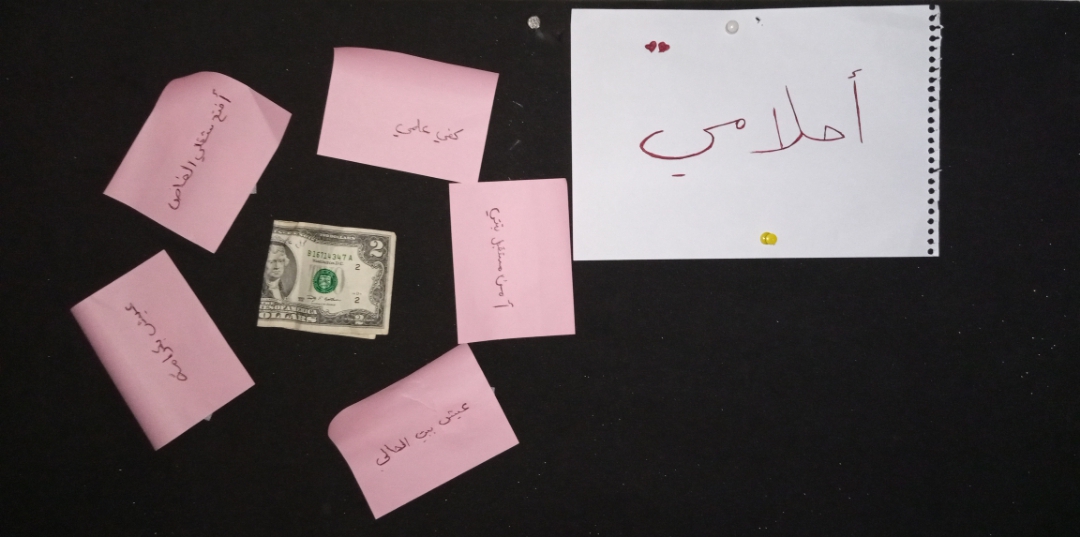

Sarah, a 22-year-old married Palestinian woman living in Ein el-Hilweh Palestinian refugee camp in Saida city. She married at the age of 20 and has one daughter.

The picture reads: My dreams are: complete my education; have my own business; live with dignity; live in a house of my own; secure my daughter’s future.

I used to have dreams. I dreamt of completing my education and opening my own beauty salon. I dreamt of a life with dignity and a secure future for my daughter. The crisis has destroyed my dreams. Life in Lebanon is now one endless stream of humiliation and I feel nothing but sadness and fear for my daughter. We have no access to education, to health care, to work. We struggle to have enough to eat. Refugees can hope for nothing other than to leave this country, where we have to beg and kiss hands to survive.

Sexual harassment

Farashi, a 17-year-old in-school Palestinian girl living in the Ein el-Hilweh Palestinian refugee camp in Saida city.

The crisis has made sexual harassment a much bigger problem inside Ein el-Hilweh. Boys and young men have lost their jobs and they are taking out their frustration on girls. There is nowhere girls can go—not even to school–where we are not subject to catcalling and unwanted touching. Some girls are even harassed and abused inside their homes, by male relatives who now have nowhere else to be. Although some people say this is ‘only words’ and ‘not violence’, it makes us terrified to leave our homes because we know that we will be blamed for ‘inviting’ it. Girls are stressed and anxious because of how we are treated. Parents should talk to their daughters and teach them how to defend themselves and reassure them that this is not their fault. The police should enforce the laws, because girls have rights too.

Basmala, a 20-year-old young Syrian woman living in an informal tented settlement in Baalbek. She married at the age of 15 and has two children.

Syrians have no rights in Lebanon. If we try to complain—about anything—then the police tell us that we should just go home. For those of us who work in the fields, there are no breaks. If employers think we are working too slowly, they beat us. The situation for girls and women is the worst, because employers touch our breasts and tell us that we are sexually arousing. Even our own relatives and the field supervisor will not protect us, because they consider it more important to keep the employer happy. One day my employer asked me to make him coffee. Then he tried to hug me. My own mother-in-law saw the whole thing and only laughed, so that he would not start shouting at her. Some employers pay girls, with money or vegetables, for sex. Because girls need the money, and know that if they refuse they will be fired, they say yes. We girls hate going to work.

Household violence

Samira, an 18-year-old married Syrian girl living in a collective shelter in Baalbek. She married at the age of 15 and has two children.

Nearly all Syrian marriages involve violence. Girls are beaten and insulted if they did not cook a favorite meal, if the house is dirty, or if they try to refuse sex. Even on the wedding night, when many girls are afraid, girls are beaten for not being pleasing enough. Words sometimes hurt worse than beatings. Husbands live their lives as if they are single, and make wives feel as if they are worthless. Girls do not get support from their own mothers. Mothers tell girls it is their job to please their husbands and that they should obey in all things. To solve the problem of violence, organisations need to raise women’s awareness of their rights and provide safe spaces and financial support. The government should enforce the law and protect girls.

Karam, a 19-year-old in-school Lebanese boy living in Baalbek.

Parents in Lebanon beat their children everywhere, even on the head and the face. Boys are beaten more than girls, because parents think it will make them ‘real men’ when they grow up. Mothers beat their children even more than fathers—though fathers will step in and beat children if mothers ask. The impacts of this violence are not only physical, they are also psychological. Constant violence destroys children’s self-confidence and makes it more likely that the children themselves will use violence. There is more awareness these days about violence, mostly from TV, but no parents are ever prosecuted for child abuse. This is because the government’s authority does not extend to areas of the country that are controlled by clans. To prevent child abuse, there should be awareness courses for couples before they get married, so that they understand what violence does to children. Children should also learn, at school and from a young age, that they have rights. It is also important that the state stand up to the clans and protect children.

Access to education

Shams, a 19-year-old married Syrian girl living in a collective shelter in Baalbek. She married at the age of 16 and has two children.

Syrian children do not attend school anymore. They cannot afford to, because the crisis has ruined everything for them just like the war in Syria ruined it for us. Even though schools are free, families cannot afford to pay for transportation or school materials. Children spend their time working or collecting anything that can be sold or used for fuel, including wood, leaves, or old nylon. They will grow up illiterate like us.

Isabella, an 18-year-old Lebanese girl living in Baalbek. She is studying nursing in a public TVET school.

The crisis has made it all but impossible for me to learn, even though I have continued my studies. Because fuel is expensive, my family can only afford to heat one room. It is very loud and I have a difficult time focusing. In addition, because we cannot run the lights, we have only candles for me to read by. This hurts my eyes and also my back, because I have to lean closer and closer to my books to see. Sometimes I wonder whether it is worth it for me to continue my education. Still, I know that I am lucky. Schools for younger children are still closed entirely—for the third year– and it is very hard for them to learn anything online. My sister does not even know how to hold a pen. Teachers just pass them anyway, even though they are not learning.

Access to healthcare

Tamer, a 19-year-old out-of-school Palestinian boy living in Ein el-Hilweh Palestinian refugee camp in Saida city.

Many people in Ein el-Hilweh camp are struggling to stay alive, because they cannot get the medication they need to treat high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes. They are humiliated in front of pharmacies, organizations, and political factions, begging for their next dose. In Lebanon, everything is about favoritism. Only the powerful can get you what you need and the powerful will not help until they are paid. Since most people cannot afford to pay, most people are made to do without. I am always afraid that I might get sick without being able to afford medicine or healthcare costs—some hospitals do not admit patients before seeing the cash first.